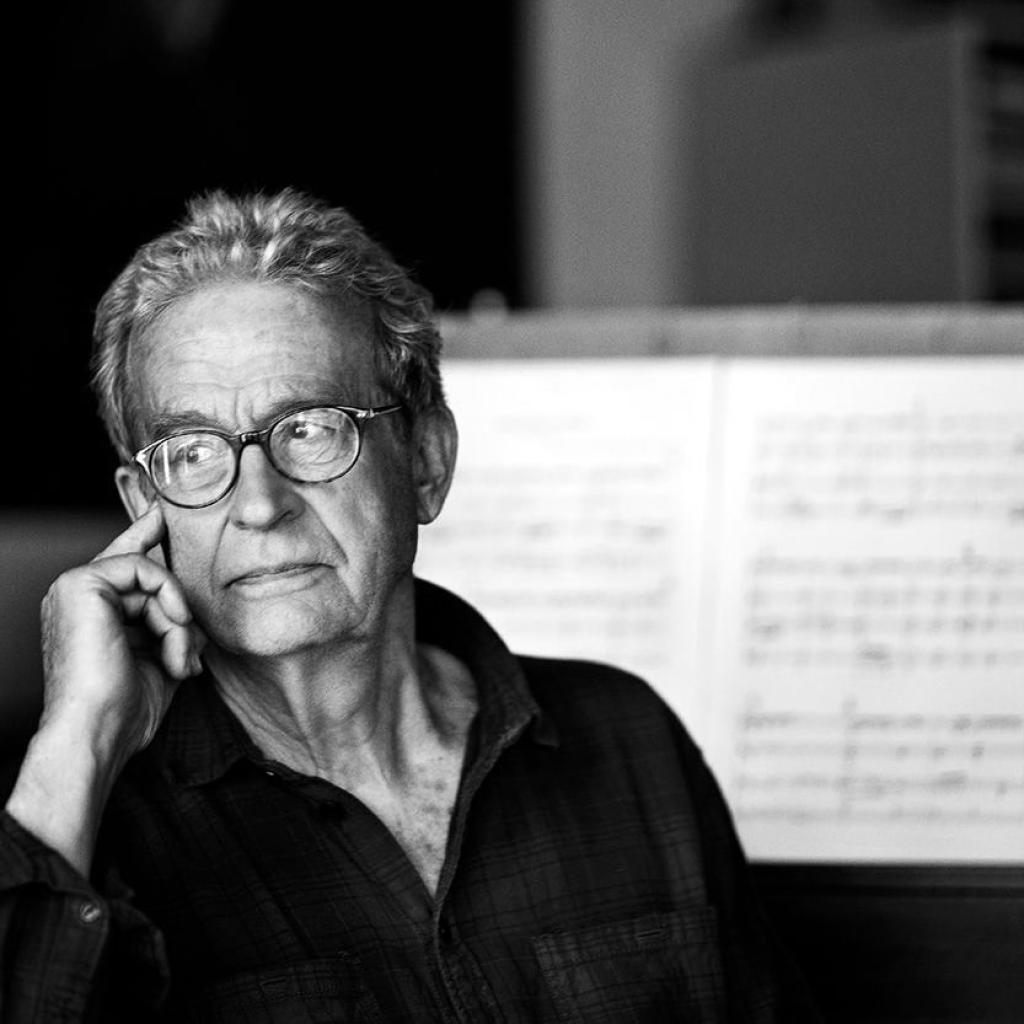

Five Views of Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen

1. A Pelle Primer

It is said that when you can be widely identified by your first name alone - Kylie, Oprah, Boris - your status as an icon is sealed. In Danish musical circles, Pelle denotes one person and one person only. In his lifetime, Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen managed to unite every faction of progressive Danish music in admiration. Today, there are millennial and Generation Z composers who cleave to him as a symbol of creative honesty and musical originality. His works resound with the sort of authenticity many better-known composers will never get near. Plenty of his music is recognizable as his in an instant, as much for its familiar ticks and devices as for the strength of its conviction and its clear sense of sound, procedure and purpose.

For all its wondrous sprawl and absurdity, Pelle’s music has always been relatively easy to rationalize - though one objective of this article is to look beyond the associations and descriptions we normally apply to him (partly by quoting his own words). To my ears, rationalizing Pelle’s music only increases its resonance and breadth, however much that music is the product of a rampant and borderless imagination.

Every serious artist, nonetheless, erects foundations on which their own endeavors sit. After Pelle’s studies at the Royal Danish Academy of Music with Finn Høffding, Svend Westergaard and Vagn Holmboe, early works were shaped by the big figures of the previous decades: Bartók, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Ligeti, even Sibelius. The string quartets, a medium that stayed with the composer his whole career, chart this process helpfully; note the style of the first three quartets, all written in 1959.

Into the 1960s, Pelle began to find his true voice. The result was a greater focus on the fundamentals of time and rhythm - from an insistently vernacular perspective - and a developing sense of the absurd handled with a childlike lack of political agenda. In 1964, Pelle completed the score Mester Jakob. It deconstructs the nursery rhyme’s well-known melody and hands the bits and pieces to a timid bassoon, which worms its way back and forth attempting to discover how it might put those pieces back again. All the while, the bassoon has to negotiate the various counsels of a larger ensemble that knows far more about the world. In 2016, Pelle described the piece’s ingredients to the filmmaker Birgit Tengberg as ‘a little birth’. He analyzed its material as ‘three notes circulating around. Not much, but enough.’

2. Mester Jakob (Frère Jacques). Danish National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Schønwandt.

There’s a good reason Pelle was still talking about Mester Jakob 50 years after he wrote it. Much can be pegged to this 10-minute score. It introduces whole swathes of concepts central to the composer’s work: the obsessive repetition or examination of a simple musical idea; the concept of one element (bassoon) faced with another of entirely contrasting sound or persuasion (ensemble); the sense of a snapshot of the world - the diversity and activity that keeps the earth rotating and its ecosystems functioning, which the artist must harbour, contain or provide an avatar for.

The timing of Mester Jakob is significant. 1964 was the year of Henning Christiansen’s Perceptive Constructions, the cited starting point for New Simplicity and arguably the Big Bang for Danish music in the latter half of the twentieth-century (as an aesthetic re-boot, its effects are arguably still being felt). New Simplicity was the sonic answer to Denmark’s functionalist furniture design movement, decreeing that the structure of any work should be clearly audible.

Pelle saw New Simplicity coming, and then went further than most in the movement. He returned not just to traditional materials - using triadic harmonies as an equivalent to the woods and leathers of the furniture makers - but to the earth itself. His music delves joyously into the nature of noise and the sonic impulses that underpin our existence.

By the mid 60s, a ferocious and effective workshop was up-and-running in Pelle’s head. Techniques pioneered by the artist Robert Rauschenberg, the writer Hans Jørgen Nielsen, the playwright Samuel Beckett and the sculptor Jørgen Gudmundsen-Holmgreen (his father) all helped shape in the composer a creative voice that would prove wholly distinctive and disarmingly honest. The music that flowed from him from the late 1960s onwards was refreshing in the extreme, applying the communicative instincts of a street busker to the ‘concrete’ principle of music as sound. Tricolore IV (1969), which prompted boos at the 1970 ISCM Festival in Basel, extends Mester Jakob’s idea of a piece based on three notes by consisting of little more than three chords in contrasting timbres. Even now, the score sounds less minimalistic than it might at first seem; the real music exists in between those three elements, in the shifting states of tension generated by their moving around one another while remaining unchanged.

Truly, Tricolore IV is the work of a musical sculptor (incessant movement, as a musical hallmark, was yet to establish itself firmly in Pelle’s work). Sculpture and the visual arts were hardwired into the composer’s brain from the off, thanks in part to his sculptor father whose shapely works laid down the sternest challenge of form.i

Pelle was long inspired by his father’s chosen discipline. He was also influenced specifically by Jørgen’s peers - not least Marcel Duchamp, mirroring his use of objets trouvés as he brought everyday items and materials into the concert hall. Plateaux pour deux (1970) famously asks a cello to duet with a set of squeeze-bulb car horns. Three Songs with Texts from Politiken (1966) has a mezzo-soprano sing with a guitar (ensemble in a later version), but the texts are banal in the extreme: newspaper reports telling of the second rejection of a motion by Roskilde City Council; of the Danish government’s debating of a new finance bill; of the centenary of the shipping line DFDS. The work could be described as a prototype for Pelle’s masterpiece for choir Konstateringer (1969), in which the whole classical idea of ‘setting’ a text is inverted. In this piece, words themselves form the music, rather than using music as a vessel.

These were not gimmicks. They were tools put in service of creative ideals. Specifically, of the post-Cage principle of a return to the idea of sound freed from the trappings we have come to associate with ‘music’, even if those trappings might be a byproduct. Like Cage’s, Pelle’s work underscores the living beauty in the raucous and the naïve and affectionately mocks notions of compositional tradition. Good poetry and good music get in the way of each other, concluded Pelle - the rationale for setting plain texts from the middle pages of a newspaper and delivering ‘total music’ as a result. As for Plateaux pour deux, ‘there is nothing wrong with the car horn,’ the composer told me in 2014; ‘it’s okay, it’s a fine instrument, it has a very refined sound.’

Woven into those instincts was Pelle’s urge to distance himself, as far as possible, from the refinement and aspiration of composers from the past - composers whose music he adored but whose footsteps he heard so prominently in his ears (Bach and Mozart among them). Much of his work did indeed owe a great deal to First Viennese School thinking, albeit refracted. The principle of combining contrasting elements that must then find a way to exist and breathe together, even via some form of gingerly argumentation, is surely derived from Sonata Form. In Pelle’s music these contrasting elements often run in circles around each another, one struggling to survive before emerging with the confidence to say something - even if the responsibility of that predicament leads them to say nothing at all (a clear response to Pelle’s guiding inspiration Samuel Beckett).

From the 1970s, these principles of unlikely coexistence started to be realized through more elaborate musical structures. Perhaps prompted by the fertile restraint of the series of Tricolore scores, Pelle began to work more intensely with delimited spaces and systemic devices, including a mirror system and his so-called ‘tone sieve’ system, both allowing for hidden melodies and fragments to emerge (often fragments from other works, sometimes by other composers) as if ‘in relief’ from foregrounded patterns or schemes.

In the acoustic version of Mirror II (1973), an orchestra is only permitted use of notes from two symmetrical outward sequences emerging from a central axis (the D above middle C), 21 pitches in all. The further away from the central D axis we get, the more free-flowing the notes become, ‘like signals’ in the composer’s words. This delimited space was a way of provoking conventional harmonic tools by pushing them out onto a tightrope - but not, importantly, discarding them completely.

An extended version of the same tone grid is deployed in Symphony, Antiphony (1977) but is here stretched to its limits not so much by the desire to upend harmonic convention as by orchestral exuberance and absurdity - the beginnings, perhaps, of the bustling rhythmic bricolage the composer would come to describe as ‘jungle baroque.’ The appearance of the occasional piano ragtime in Symphony, Antiphony again echoes the objets trouvés of car horns and newspaper texts.

Vital hallmarks are emerging here: the composer’s piled-up chords built on the interval of the fifth (often with added sixths) and the music’s distinctive onward tread and animalistic heartbeat - the latter a feature that would develop into something wholly idiosyncratic.

In Pelle’s music of the 1980s, we begin to hear a greater sense both of physicality and humanity. The composer long fretted over form, but appears to have concluded in this later decade that form might possibly bypass the traditional idea of a schematic floor-plan in favour of a more organic sense of balance - between opposing impulses, etiquettes, timbres or agendas. The thread of Pelle’s 14 string quartets, in particular, reflect this - as well as the composer’s increasing concern with the living presence of the musicians who would play the notes; his bonds with these people and personal understanding of them. That is particularly apparent in the case of the string quartets numbered 7 and up, written for the members of the Kronos Quartet.

By now we have roughly assembled the ingredients of Pelle’s sound universe. It is the mark of a great composer that many of these fundamental principles blossomed but effectively didn’t change. In Pelle’s case, much of his music didn’t alter in fundamental structure either, even if its upholstery, scale and gait could appear different. If the composer’s stance as a disruptor sharpened with age, its realization remained somehow laconic - or became even more so. What could be more quietly, unobtrusively playful than his late tendency to write modular works in which a new score might consist of two others played at the same time (third movement of Tryptikon)?

2. The Pelle Sound

To continue the idea of ‘rationalization’, it might be argued that whenever Pelle started out on a new work, he did so with similar fundamental expressive aims. The challenge was deciding how to realize that through instruments - and with which instruments. This, in turn, is what delivered such a diverse output. ‘You can’t put every sound in one piece,’ the composer told me in 2014, ‘so you have to decide [in a specific piece] which sounds will meet each other.’

Sometimes that decision would be taken out of the composer’s hands by the rubric of a commission. Every time, however, there would be plenty more additional conscious decisions to make before embarking upon a new score. What Pelle surely did not decide on was how much of himself to put into a piece. That happened unconsciously. And we tend to get a lot of him. The more time he spent with his material (plenty), the more that material would come to resemble him - even when he was quoting someone else.

Often Pelle felt the temptation ‘to seek those areas that are called stupid,’ which might have influenced the chosen instruments in the first place (the car door of Traffic, 1994, the car horns of Plateaux pour deux). The wonder of his works is that while none of them take themselves particularly seriously, plenty become poignant, emotive or deeply serious by default. If his works provoke, and some do, it is rarely for the sake of provocation or to the detriment of a particular score’s emotional residue. Listening with concentration, we hear a body of work in sympathy with whole rafts of the planet’s species - music whose unerring sense of rhythm enshrines a clear heartbeat and a living pulse; whose numerous displacements and distractions speak of the imperfection, coyness, exuberance and confusion of life as a mammal.

Repetition is vital. For Pelle, it was a means of shaking the thematic tree. As Mester Jakob suggests, it was one of the composer’s fundamental tools from the start and he proved consistently able to use it resourcefully. He could even use it by stealth, as witness his extensive use (and abuse) of the ‘ground bass’ in the string quartets of the 2000s. He could use repetition with striking beauty, elevating it above the status of a tool (and a potentially boring one), tinting it with poetry or rhapsody even in its underlying banality. Central to Pelle’s project was the constant prompting of us to consider our place in a world overrun by both banality and beauty. He had a neat way of crossing the divide between the two, often turning the former into the latter.

He could also go the other way, mining the apparently banal from within the overtly beauteous. His response to Schubert’s Moments Musicaux features the stuttering repetition of a fragment of the Viennese composer’s tune - a judiciously chosen corner of it, in fact, which can sound mechanical but actually takes on the quality of a secular prayer. The fact that the piano trio playing the piece has had such trouble singing out the melody in the previous movements only increases the impact.

Moments Musicaux (2006) sounds like the deftest of musical fairy-tales. It tries to be irreverent by getting down and dirty: taking Schubert and chopping him up. It ends up sounding with an equivalent emotional power to the original in its stop-starting and its frank admittance that humans can be damaged - that they might just need encouragement some of the time. The piece reinforces the English poet Simon Armitage’s potent reminder to artists that ‘to err is to be human, to be born is to be a hypocrite, and to recognize and admit one’s inadequacies is to come as close to triumph as is humanly possible.’

In Pelle’s Moments Musicaux, Schubert’s melody eventually makes itself heard, rather like Mozart’s does in Pelle’s Og (2012). Like the bassoon of Mester Jakob and the cello of Plateaux pour Deux, it manages to get the door open and enjoy a moment in the sun. In Moments we also experience Pelle’s cherishing but judicious attitude to tonal, triadic harmony. That tendency traces a line through plenty of modernist Danish composers before and after him: Carl Nielsen, Bent Sørensen, Christian Winther Christensen et al.

For Pelle, treating Schubert’s melody as a toy was paying it a compliment. As a man, the Dane long fought to retain his childlike impulse, not in the out-dated rebelliousness of a faded rock star but in allowing himself to climb up to what the English artist Grayson Perry has described as the ‘tree house of creativity’ - a place where the creative act and a personal need for it rules supreme; where the imperatives of adulthood are put on hold. For Pelle, it was a way of keeping impulses fresh and undimmed - a method for retaining the spirit and wonder inherent in his music.

If banalities could seize hold of the discourse in Pelle’s work, and be held aloft in fascination, so could they in person. I think of those moments in the film portraits of the composer made by Jytte Rex and Birgit Tengbergii when he celebrates the everyday: spreading leverpostej on bread; suddenly preoccupied with dusting. Rex’s film captures the composer moments after being presented with the Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie-Carl Nielsen Prize, stepping off the podium repeating the phrase ‘skattefri…skattefri’. It was an echo of the behaviour of much of his music: alighting on a seemingly banal or bureaucratic detail, elevating it with repetition, charging it with a sort of ironic significance, creating in it something that can question and enchant.

Always in these films, Pelle seemed to be drawn to the edge - to committing the cardinal sin, in front of a serious filmmaker, of outing himself as an ordinary human being by talking about cobwebs, lunch or tax. I see it as a sign of his humanity in all its ordinary wonder but also a parallel to his musical tendency to push instruments out into unsafe spaces; to throw instrumental groups into unlikely coalitions that writhe and wriggle like ferrets in a sack. To ask people, much as Carl Nielsen does in Maskarade and other works, to be something other than that which they think they ought to be.

In a number of Pelle’s works, we meet a protagonist: an organism with a biological pulse and affable spirit that sets out to make its way in the world, come what may (most of the time it appears to be a furry mammal, but one that demonstrate a reptilian style of movement, close to the forest floor). Our protagonist might be heroic, shy, gregarious, or self-conscious. It might even be self-critical.

For Violin and Orchestra (2002/2003) is a fairytale, a road movie, perhaps a symphonic poem but apparently not a violin concerto. The violin strikes out with wide-eyed innocence only to encounter various blocks of instrumental sound along its path: diatonic string clusters, Arabic-sounding winds, a jungle of brass. Even as they gain autonomy, these blocks prove able to merge their anatomical differences of timbre, rhythm, expression and thus meet with the soloist in various guises: challenger, friend, supporting landscape or hostile landscape. Like the ensemble of Mester Jakob, the orchestra seems worldly, savvy and wide-ranging to the solo protagonist’s more innocent desire to get on and (eventually) get out.

This tells us much about Pelle’s imagining of the wider world and its species, and his ability to layer those visions within his chosen ensemble - to set a complex musical ecosystem in train and then focus-pull into particular elements of it, letting us see or hear bits of the puzzle that had been hitherto concealed but active all along. It was a technique derived from baroque concerto grosso form, which in time delivered one of the composer’s most absorbing journeys through clearly differentiated landscapes, the literally-titled Concerto Grosso (1990 rev. 2006) for string quartet and a companion orchestra with only two double basses in its entire string section. After its journey through what feels like a world of varied musics, the characteristic thrashing and clashing grows weary. A raucous culminating cacophony is followed by glistening, radiant benediction from the string quartet alone.

3. Pelle, the Real World and the Whole World

That we live in a world filled with cursing, cussing, dirt and disorder only stimulated Pelle. His music is filled with the stuttering and faltering of real, imperfect life. His works are frequently interrupted by themselves, as if they are playing out beyond the confines of an orderly concert hall. They can seem self-conscious and shy. Sometimes, a score’s central protagonist will get lost, chase its tail or fail to communicate altogether.

In music stripped of affekt and affectation, Pelle amplifies the truths of a world that can be ugly and meaningless - a world that is often more interesting in the gutter than in the stars, that ‘thinks with the wise but speaks with the vulgar,’ as Ralph Waldo Emerson once put it. But challenging philosophies were fierce stimulants for the composer, too. ‘The catastrophe of meaninglessness has something deeply liberating about it,’ he said in 1992, reflecting on the creative awakening he experienced on delving into the work of Samuel Beckett some forty years earlier. The joy of it, surely, is that meaninglessness invites scrutiny: we’re more likely to flip something meaningless over, dissect it or shake it rigorously, just to be sure nothing we’ve missed falls out.

A plainer truth is that there’s something inherently ‘realist’ in the idea of a work of art that pivots on a close-quartered meaning rather than resting on a grand conceit. When I was sent to interview Pelle by the Guardian newspaper in 2014, we sat in a café overlooking Blågårds Plads and began to analyze his piece Run (2012), which had just been recorded by the London Sinfonietta (Pelle was of the opinion that the London orchestra had initially believed, in his music, they were ‘in bad company’ - a recurring theme in discussions of the reception of his own music). I read out part of the album’s liner note - a detailed, eloquent musicological analysis of what happens in the score written by Paul Griffiths. ‘It’s a man running,’ was Pelle’s contribution. ‘Maybe he’s a man in a condition, who has to run. He is being whipped to run. I think actually he is a fat man. Yes: it’s a fat man running.’

The realism in Pelle’s music extended to its very Nordic view of a natural world largely shorn of Romantic projection and allegory. ‘I am told that my music sounds strange, to which I reply, doesn’t nature sound strange?’ he once said. His hunt for musical realism led him back, time and again, to nature in all its scientific stringency and everyday banality – to waves and tides, to mudflats and reed-beds, to bird-houses and forest floors. The natural impulse is found in almost the entirety of his oeuvre, whether a piece calls for human voices inflected with avian song or for a string quartet itching and scratching itself like a shuffling quadruped (see the string quartet and vocal works No Ground, Green, No Ground Green, New Ground and New Ground Green, all from 2011).

Sometimes, the music’s view of nature is forensic in its realism, even if there’s a dash of humour and fantasy thrown in. Both are found in the ‘Bats Ultrasound’, ‘Elephant Octaves’ and 'Cattle Egret' of Fire madrigaler fra naturens verden (2001). Elsewhere, the process is more subliminal. The shallow dunes and hills of Pelle’s beloved Samsø and the rumbling of the Kattegat Sea at its shoreline lay constantly under the composer’s consciousness and were ‘likely to surface at some point or another,’ he told Birgit Tengberg in 2016. They’re surely present in the throbbing that underpins even a relatively light, quiet piece like For Cello and Orchestra (1996) and are literally transplanted in the sampled coastal sounds of his String Quartet No 9 (2006).

Pelle was a realist when it came to his work and its effectiveness. ‘The pieces I’m rather happy about – you say that because you’re never completely happy – are those in which the conception and the way of doing it has been clear to a high degree,’ he said in 2014. ‘The pieces I’m not so happy about have too many things in them, which means I’ve not been completely aware of what I was doing.’

He once commented that ‘I want to be able to look my own time in the eye.’iii That desire, and the impetus to be clear, was realized with extreme potency in the two-movement work for baritone and string quartet, Moving, Still. The steampunk first movement, ‘Moving’, journeys mechanically in its setting of Hans Christian Andersen’s travel-themed fairy tale In a Thousand Years. The second movement, ‘Still’ has a pure, untrained and purposefully non-Danish voice sing, in the original Danish, Andersen’s poem In Denmark I was born. The melody, introduced and delicately harmonized by the quartet, acknowledges its antecedents by Henrik Rung and Poul Schierbeck but is Pelle’s own - proof of his considerable abilities as a tunesmith.

Soon that melody starts to occupy a distinctive space. The singer uses a sampler to loop his own voice, creating a vortex of echoes that feed the poem’s nostalgic visions back against themselves. The quartet’s underlying harmony shifts in style, from Lutheran chorale to Slavic prayer, to boogie-woogie, to the Hassidic and eventually to the Arabic. It only takes a few flattened notes and ragged rhythms here and there, with a touch of elegant ornamentation from the singer, and the ear believes it is hearing an Arabic song.

‘We live at a time when Danishness has become a theme that arouses malaise and claustrophobia,’ wrote the composer in the liner notes for the Kronos Quartet’s 2008 recording of Moving, Still. ‘I wanted to draw attention rather rudely to the fact that Danishness is not an immutable entity, but is colored by innumerable influences from the outside.’ There was added allegorical power in having an English-born knight of the Dannebrog, Paul Hillier, deliver the text. In 2014, Pelle put it to me directly: ‘I’m not a fan of Denmark,’ he said. ‘I think we have so many bad qualities, notably being a little too relaxed when it comes to treating other people, the people coming into this country.’ The comment echoes Carl Nielsen’s own condemnation of the ‘spiritual syphilis of nationalism’.

Pelle’s music drew on sources from the music of the Pygmies to Mongolian singing traditions and African drumming, as well as those closer to home. He might have considered his music borderless. A non-Danish observer familiar with the country might conclude that despite its international relevance and universality, his music is quintessentially Danish - in its functionalism, its desire to build big from small ingredients, its insistence that the everyday can be as beautiful as the palatial, in the ferocity with which it seeks to protect democracy through incessant questioning of authority, and, perhaps most obviously of all, in its quest to tap those notions of health, happiness and togetherness that apparently remain Denmark’s grand national project.

4. Pelle and Bach, Mozart, Schubert, Mahler, Ives, Stravinsky

The iconoclasts of the 1960s and 70s were schooled in the ins-and-outs of what it was they were kicking down. Is it a good or bad thing that some sense of the five centuries of music that went before them is baked into the psyche even of a composer determined to re-write the rules? In Pelle’s case, the presence of composers from Bach to Ligeti - not to mention his peers in Denmark - is impossible to ignore. Not only did those composers lead Pelle to consciously steer his art towards very different (even opposite) goals; they also, counter-intuitively perhaps, made their presence felt in the actual fabric of his work - either through shaping his aesthetic or quite literally furnishing parts of his scores.

Hearing these figures in his head was as tortuous as it was inspiring for Pelle. ‘If you decide to be a composer you are childish,’ he told me in 2014. ‘If you were very clever you wouldn’t do it, because you would see the problems and the impossibility of being together with Mozart and Bach.’ He spoke frequently of the absurdity of opting to pursue a profession in which you’d be compared to great minds. He did so knowing how important it is that each age contributes to a continuously developing art.

In our conversation in 2014, Pelle elaborated on the idea. ‘If you listen to Bach, what the hell is going on? It’s so overwhelming that you find yourself astonished by this information, so this astonishment is part of the joke. It’s not just a reaction – it sounds beautiful – it’s that you can’t understand why it sounds so beautiful. It’s impossible to understand. But [that is]…a rather fruitful situation to be in. I think all composers know about not knowing exactly what they’re doing, and they feel the temptation of not knowing. If you knew completely what to do you would be bored. So the anxiety, the nervousness, is rather inspiring. I think all artists know this nervousness in relation to their material; whether they are on the right track or not, when every day a new question has to be solved and you do not know what’s going on the next day.’

Bach did more than push Pelle into that stimulating creative hinterland that leads to music of genius and exuberance; he very tangibly informed the structural weave and lifeblood of so many of Pelle’s works. Think of the throbbing instrumental discourse that opens one of Bach’s Passions, or the gregarious gameplay that launches his first Brandenburg Concerto. The biological quality of the ensemble’s collective heartbeat (irrespective of the chosen tempo) and the inevitability of the music’s gait are refracted in the chuffing, shuffling and motoring-forward of so many passages in Pelle’s work.

Mozart’s influence worked entirely differently. This was a composer to whom Pelle set himself purposefully at odds, at least in terms of etiquette. Mozart represented a set of musical codes and boundaries Pelle consciously distanced himself from by craning those very things directly into his own scores for contrast. In the final movement of the piano concerto Plateaux (2005), the soloist latches on to a chunk of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No 25, apparently oblivious to the surrounding flora and fauna of Pelle’s fairytale orchestra. That orchestra is then forced to become accustomed to and even comfortable with the piano’s Mozart, to the extent that it begins to build its tonal space from thirds. It’s a typical technical resolution from the composer and in this case a particularly beautiful one.

Part of this was Pelle proving he was not afraid of beauty - his own means of quelling the musical tempests that swirled about his own head. As he commented to Anders Beyer: ‘the eternal dream of man is to experience peace and calmness. More and more often now, I write music about that dream. I don’t think you’d call it nostalgia.’

Part of it, though, was Pelle’s own desire to disassociate himself from the sort of gallantry and politeness that was anomalous to him - indeed, to life in twenty-first century Denmark. In Og (2012), written to mark the Kierkegaard bicentenary, we hear imposing slabs of D minor grandeur from Don Giovanni but it’s Zerlina’s elegant and so very human music that exercises the most significant magnetic pull on the work. The chafing impoliteness of Pelle’s original music gradually gets out of the way until that timid bassoon - a reincarnation of the character we heard from in Mester Jakob - can finally annunciate the melody of ‘Là ci darem la mano’. ‘One tidies up,’ Pelle said to Birgit Tengberg in 2016, referring to this moment, ‘and then there’s room for Mozart.’

Schubert we have dealt with to some extent already. Pelle’s attachment to that composer’s Moments Musicaux not only expands what we know about his admiration for the First Viennese School but also sheds revealing light on it. We hear how close Pelle’s work is to the Schubert of Moments Musicaux, whose music so often overlaps with the vernacular and speaks as if from the front of the mouth.

To an extent, we can address the looming figure of Gustav Mahler through the intermediary of Charles Ives. In both composers’ scores, marching bands invade the musical discourse as if from the street. The shock of vernacular material appearing unwashed in a formal environment is felt just as fiercely in Pelle’s music (and Carl Nielsen’s). The synergy with Mahler is perhaps more subtle and more interesting. It concerns the philosophical landscape of a work - the idea that while for Mahler ‘a symphony must be like the world - it must contain everything’, for Pelle, any piece should attempt in some sense to give a snapshot of the world in all its spiraling chaos and diversity (but within clear, even neat boundaries).

In this case, that means music that looks up at the world as if from ground level even if the surrounding landscapes present what could be described as an ‘overview’. The ‘muttering in the mud’ that we so often hear in Pelle’s works presents a vital advancing on the idea of landscape in Nordic music - of the long tradition of the bass pedal note underpinning Grieg’s broad horizons or Sibelius’s subtly shifting riverbeds. In Pelle’s music, the sense of subterranean rumbling is not something from which to build towers into the sky, but from which to explore the very ground we’re on.

What we hear in those works now, particularly the orchestral works, echoes what must have been heard, with immense shock, when Mahler made his first excursion away from blanket lyricism towards the abruptness and impoliteness of a work like his Symphony No 5. Suddenly, audiences heard an orchestral language that was willing to indulge dirty, grinding conflicts and painful truths. It was a view of the world as Mahler saw it that absolutely laid the ground for the instrumental distortions, scrunches and obsessions we hear in Pelle’s orchestra.

Discussing dead composers in 2014, Pelle had this to say: ‘Charles Ives was a fantastic, wild and strange composer, putting those things together. He was mad and fresh; his madness was fresh. But when I listen to Stravinsky I have this feeling that I only have when I listen to Stravinsky; it’s as if a hot electrical current has been put directly onto the nerves. This nervous rhythm, constantly moving without going anywhere. But at the same time he’s Russian and he also has this Asian quietness, calmness. Perhaps that Asian quality enables him to be nervous and calm at the same time.’

Stravinsky’s largely posthumous influence on New Simplicity is difficult to overstate. You don’t have to listen far in many of Pelle’s chamber works - I instinctively think of the ‘Ground’ series of string quartets - to hear the balance, cool objectivity and etched perfection that Stravinsky prized above all else. The comparison exists in the crystalline quality of the two composers’ musical counterpoint, their shared sense of restless movement and internal activity and their trust in the white space that surrounds the notes or even comes to dominate them. But it exists, also, in the two composers’ sculptural focus on the constituent moving (or not moving) parts of their work as ‘objects’. Only when given autonomy can these objects interact with ‘real’ meaning.

5. Pelle as Carl Nielsen’s True Successor

Carl Nielsen and Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen: two Danish composers who existed in Copenhagen and its environs less than a century apart. Many of their human experiences would have been common ones. The electric trams that rattled through the capital in Nielsen’s day screeched their last in 1972 - the year, appropriately enough, of Pelle’s electric guitar work, Solo.

One common biographical detail stands out more than most. While Nielsen spent 16 years in the employment of the Royal Theatre on Kongens Nytorv, less than forty years after the great icon’s death, Pelle was working as a technician in the same theatre. Manual, physical work suited the composer. Many of us could have imagined the octogenarian Pelle launching himself with gusto into a physical task that younger colleagues would have considered beyond them. I can’t approximate the feelings of Pelle’s close friends and family at the time of his death. But as someone who knew Pelle a little - thanks mostly to his music - conceding to mortality just didn’t seem like a physical plausibility. Until, of course, it started to look like an actual inevitability.

That was the impression I got from the composer when we met on Blågårds Plads in 2014. We talked then, unexpectedly, about Nielsen. ‘Nielsen is one of my favourite composers. And I know why, because he has a freshness which is very rare, and is also odd,’ Pelle observed. ‘Much of his music is not accepted in France and Italy, because they do not understand this square and rude and fresh style.’

Can he be described as vulgar? ‘No, I don’t think he is vulgar. He is common – he’s not afraid of being common. But in being common he is still original […]. Sometimes I prefer him to Brahms, which I know is a ridiculous thing to say as Brahms is a fantastic composer. But everything is in the right place with Brahms. And you have this colour, sort of like this table here. It’s like a very deep brown, mahogany desk in the Ministry of Justice. Brahms is on the right side of the desk – so convincing, so right, so beautiful in his heaviness. Carl Nielsen is on the wrong side: a little out of tune, the naughty boy, not the cleverest in the class but definitely the most inventive. You couldn’t confuse him with anyone else.’ Pelle could easily have been describing himself.

In a pertinent echo of Carl Nielsen’s lifelong quest to drag song and symphony back down to earth, Pelle’s music endears itself more downwards than upwards. It concerns itself with a common experience and is never afraid to walk mud into the concert hall or do the ostensibly ‘wrong’ thing. Only in this part of Scandinavia would that aesthetic approach have worked for sixty years without sacrificing major opera and symphonic commissions (though it might just have cut the mustard in Finland too). Both Nielsen and his successor strived to side with the man on the street or even to embody him, however difficult it proved from within the confines of Denmark’s creative establishment.

Nielsen’s continued relevance lies in his ability to write music that was somehow about Denmark, but was even more about a wider world which could always hear how brilliantly he was progressing the language of an art form owned by no nation in particular. In his disruptive symphonies, themselves full of invading forces and distinctive ways of tapping musical momentum, we hear premonitions of Pelle’s own musical mechanics: the insistent shuffle that carries his music onward; the sense that anything could lie around the corner - a ragtime, a lullaby, a shout or a musical cul-de-sac that arrests the discourse altogether.

As the proverbial child playing with dynamite, Nielsen refined his strangeness in much the same way Pelle did. Chaos can’t be musically successful unless it is somehow tamed, defeated or at least compelled to play by certain rules - the process at work in whole swathes of Pelle’s music as well as Nielsen’s later symphonies. Eccentricity is boring without form and focus. And if music must ‘be like the world’, as Mahler suggested, then it will sometimes sound ugly. It will scratch, sniff and shuffle as well a sing. It will address banalities. And it will delve joyously into the nature of noise and the sonic impulses that underpin life, humour, speech and conversation.

Notes

- Beyer, Anders: ‘To Combine the Savage with the Refined,’ Dansk Musiktidskrift, conversation with the composer. (‘I have kept a childish and naïve outlook to my work from my father, but also inherited from him the quest for the perfect form,’ the composer once said; ‘I know that it can’t be found, but I shall continue to try.’)

- Jytte Rex: Music is a Monster (2007); Birgit Tengberg: På tværs (2016)

- Beyer, Anders: ‘To Combine the Savage with the Refined,’ Dansk Musiktidskrift, conversation with the composer